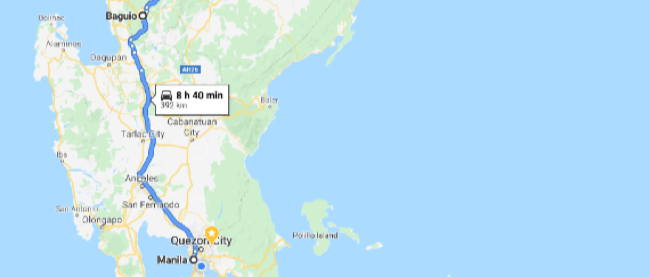

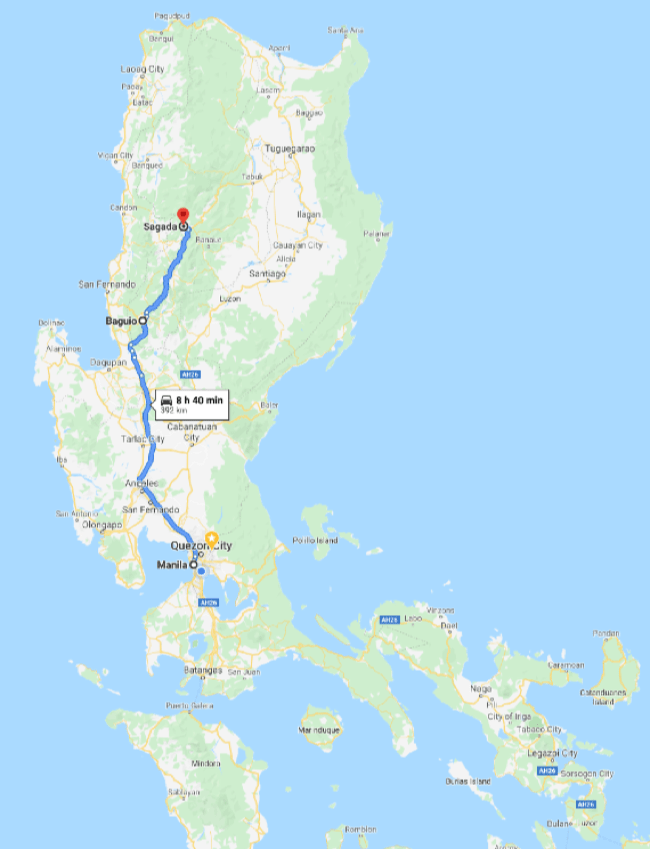

“Let’s go! Road trip!” said Antonette. “Sure, I’ll drive,” I said, not realizing the trip would take six hours by overnight bus and then another six hours by car traversing the highest mountain roads in the Philippines. Was it worth it? Yea. Photos and story here.

We left Manila at midnight and arrived at the mountain metropolis of Baguio at 4am at a roadside bus drop-off. A taxi driver offered to arrange a place to nap in a transient house (guesthouse for locals) while we waited for delivery of our rental car. I handed PHP1000 ($20) to the taxi driver. The place was squammy but I got to rest. The rental car guy showed up at 7am with a dusty Toyota Avanza, smiled, handed me the keys, collected PHP3000 ($60) in cash and took off on the back of his friend’s motorbike. No credit card required. No insurance offers to decline. No papers to sign. He didn’t ask to see my drivers license. As we say in the tech world, “Not sure it scales,” but hey, works for me.

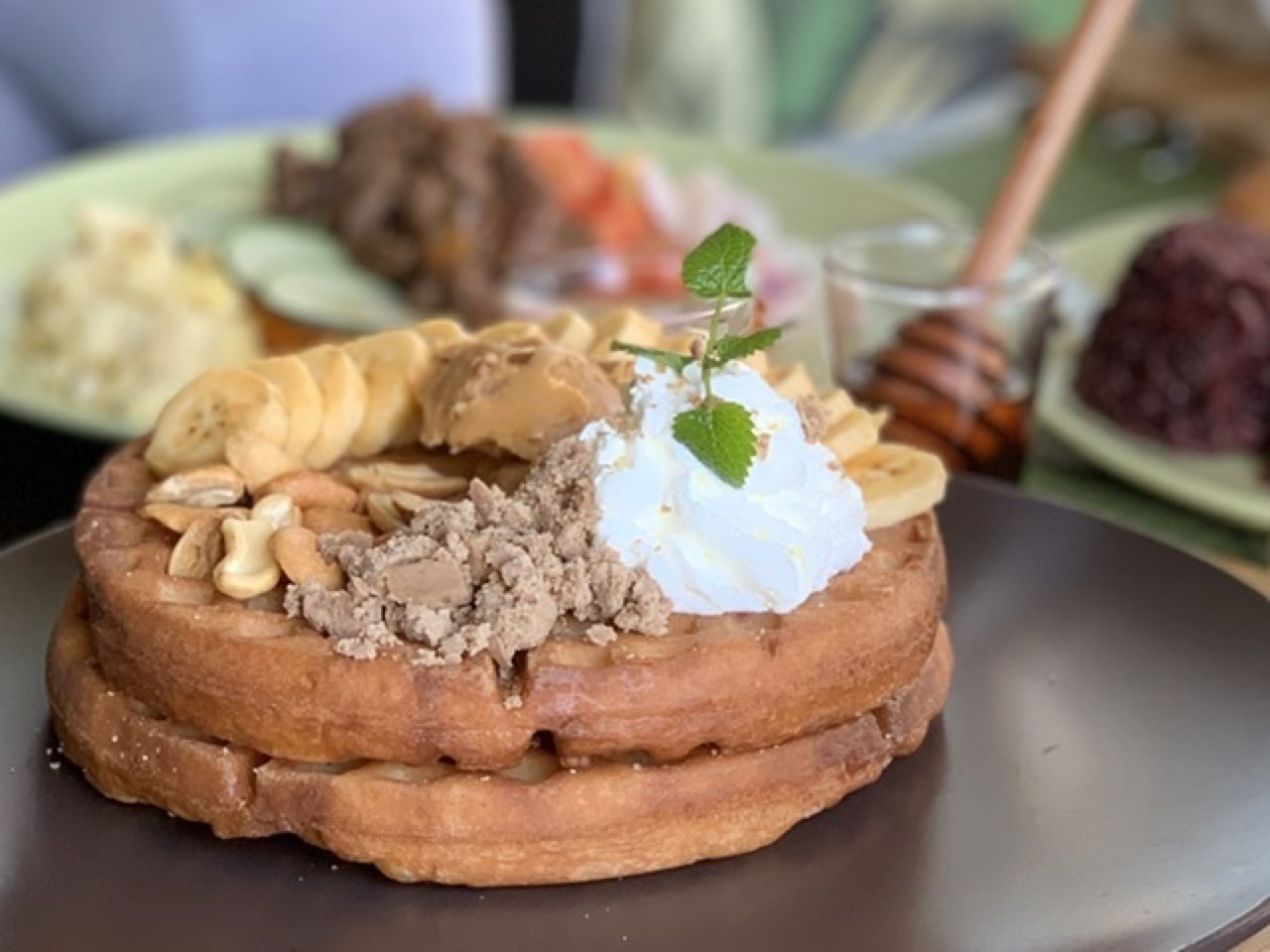

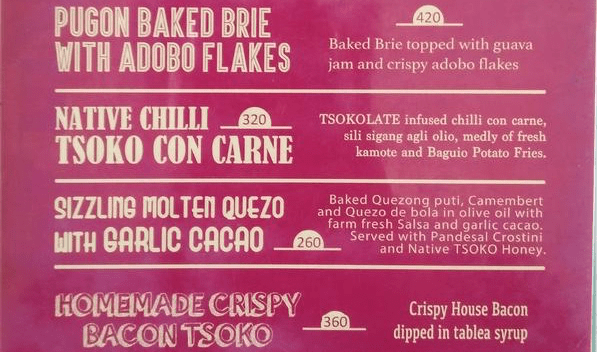

We couldn’t leave Baguio without breakfast so we made a stop at Tsokolateria, a chocolate-themed cafe. How about chili infused with chocolate? Not for me, I chose the waffles.

Baguio isn’t pretty from a distance. It looks like the worst parts of Manila dumped on a mountainside. Topped by a low-hanging cloud of smog emitted by all the diesel jeepney trucks.

I didn’t really see any views as we left Baguio, though. All I saw was the back of trucks. Baguio is the center of a busy agricultural region and trucks overloaded with cabbages move slowwwwwly. Those trucks are difficult to overtake on narrow mountain roads. Unless they break down, like this truck.

The ag trucks thinned out after we passed through several market towns on the highway.

Here’s the story of the road. Construction of the highway was started in the 1920s. It was originally called the Mountain Trail by the local people and renamed the Halsema Highway after its completion by the Americans under the colonial administration. Long before the Americans arrived, reports of gold in the Cordillera Central brought the first Spanish expeditions to the mountains and sparked conflicts with the local people of the Cordilleras. A dozen distinct indigenous ethnic groups share a Cordilleran culture which is molded by the mountains, plus a common heritage of resisting environmental and cultural destruction by first the Spanish, then the US and the Japanese, and to this day, the central government in Manila. Running through the last hundred years of history like a thread is the Halsema Highway. It’s a technological marvel of the 1920s. And like other technological marvels, it’s been both a blessing and a curse to those who use it.

We crossed from Benguet province to Mountain province at the highest point in the Philippine highway system (according to the sign and a stray dog).

Apparently it’s not really the highest point; as of February 2019 another road about 60km away was given official status as the highest road in the Philippines.

We were able to enjoy clear views of Mt Pulag. Geography lesson: It is Luzon island’s highest mountain at 2,926 meters and the third highest mountain in the Philippines (the higher mountains are on the island of Mindanao). On our return trip the next day, the clouds were low and the road was shrouded in fog, so we were lucky to see it.

At the so-called “highest point,” we were only 100km from Sagada but it took another 4 hours to reach our destination. I lost track of how many places the road was undergoing repair due to slides and subsidence.

In other countries, heavy equipment, truckloads of steel and concrete, and “tax dollars at work” balance the forces of weather, geology and gravity. On the Halsema Highway, it looks like nature is winning, as if the landscape itself resists human technology and the forces of development.

We arrived in Sagada by 3pm and checked into a guesthouse that advertised its local coffee. We were told the espresso machine was broken and toilet paper was provided only by special request. But it was quiet and the views were beautiful.

The Sagada area consists of a central village (Sagada Proper) plus small hamlets and guesthouses scattered across limestone ridges and a karst valley. Outsiders cannot acquire land and the indigenous Kankana-ey community limits development within their domain. There are no large hotels or resorts.

For dinner, we ate at the Gaia cafe, which specializes in cuisine referred to as “hippie food” where I grew up. The photo above, from the web, isn’t quite accurate as the cafe has been expanded. But the views are beautiful.

On the narrow road back to the guesthouse, our Toyota Avanza was halted by a youth group banging drums and dancing in the road. As they waved us through, we wondered if they were practicing for a cultural performance or if it was just a Friday night social thing in a community that doesn’t get good Internet.

The night was cold (for the Philippines) and we were up at 4am to meet our guide for a day of hiking and sightseeing. We left the car in a dusty parking lot that was filled with tourists and local vendors selling souvenirs and food from stalls. As far as I could tell (it was dark), there were few Western foreigners or East Asians; most of the tourists seemed to be Filipinos speaking Tagalog, probably from Manila. After hiking an hour uphill on a muddy road in the dark, guided by flashlights, we arrived at a commotion that looked like a street fair. Tourists were milling around rows of stalls lit by portable lights that sold all kinds of Filipino snack foods. We sat at rough-hewn tables and ate sopas (hot milky soup with macaroni, typically eaten during breakfast, cold weather, or served to sick people) and champorado (rice porridge blended with sweet chocolate). It was good.

I’m not yet convinced of the wisdom of hiking before daylight (which is a prevalent Filipino custom for treks) but I enjoyed having a hot snack while waiting for daybreak. We were at the top of Kamanbaneng Peak. I was told the views would be spectacular if the day dawned clear. As we finished our champorado, the darkness gave way to a uniform gray fog. A nearby promontory emerged from the fog. Everyone rushed to take photos of the non-view.

Here I am at foggy Kamanbaneng Peak with our guide Morden and my fiancée Antonette and our two friends.

As we started down from the peak, the fog started to clear and we were able to take photos of the valley below us.

Everyone had their photo taken, including our mascot Ratty.

We descended through a scrub biome (kind of like the chaparral I know from California), giving way to a beautiful pine forest with many wildflowers.

Pine forest is unusual in the Philippines, and combined with the limestone karst landscape, it gives Sagada a unique quality.

We discovered certain areas have gravity anomalies which allow easy levitation.

After our uplifting experience, we continued to the Blue Soil Hills area. The bluish-green color is due to the high copper sulfate content of the soil.

We were close to the road and a parking area where we waited for our van ride back to town. While we waited, we helped a local mom and kids shuck beans.

Back in Sagada Proper at the Episcopal church by 9am, we were ready for our second hike of the day, through Echo Valley.

Roman Catholicism is the predominant religion practiced in the Philippines. The municipality of Sagada is the only Philippine town that is predominantly Anglican with almost 95% of the population baptized as Episcopalians. The hiking trail passes through the Episcopalian graveyard, nestled below the town’s cell tower.

There’s a steep descent from the graveyard down to the floor of Echo Valley. We walked down the stairs and found a guy setting up a climbing wall.

The limestone cliffs are great for sport climbing. Antonette made her first belayed ascent on this wall. It’s a 5.7 on the climbers’ scale (a good challenge for beginners).

You can’t climb on all the cliffs. Some of the nearby limestone cliffs are used for the Kankana-ey community burial tradition.

These are the famous hanging coffins of Sagada. I’d heard about the hanging coffins and assumed they were relics of the past. I asked our guide when the last person was interred on the cliff, I figured maybe a hundred years ago. He said it was his grandfather, just ten years ago. He said scaffolding and ropes are used to lift the coffin to the cliff. Once the coffin is in place, the body is lifted into the coffin. The body and the coffin are heavy so it’s a two step procedure. The body is adjusted into a fetal position before interment as the Kankana-ey people believe we come into the world curled up and should leave the same way. I asked our guide how the Episcopalian priests feel about the hanging coffins and he said the local burial practices are accepted by the church; it’s up to the individual and their family to choose the cemetery under the cell tower or the one on the cliff. He said it makes sense to some people to be buried on the cliff where the spirit can easily find its way back to the natural world. Presumably if you want to be buried with your cellphone, you’ll choose the cemetery under the cell tower.

As we talked, a local school teacher arrived at the site with her students and gave them a talk about the coffins. Our guide said he felt the community was doing a good job at preserving its traditions. Tourism supports the local economy now. He said the ancestors were wise to choose the cliff burial tradition so the tourists would come to visit. I wasn’t sure if he was joking.

One of the other guides engaged me in conversation when he learned I was from California. “Legal marijuana?” I said yes, it’s legal in California now. He shook his head sadly, “We need that here.” In the 1990s he said Sagada was known as Luzon’s “Little Amsterdam,” due to the wide availability of pot grown in the surrounding mountains. In the last ten years, the central government has instituted a marijuana eradication program and it has hurt the local economy.

I told him I’d stopped for the PNP (Philippines National Police) roadside checkpoint at the center of town the night before. I asked him what the PNP is looking for. Drunk drivers? Pot smugglers? The local communist insurgents? He laughed. “It’s just for show so they can write up a report. There is zero crime in Sagada. You can see the jail next to the tourist office. It’s full of dust and cobwebs.”

Our guide asked us if we wanted to hike up through an underground river. We said yes and followed a creek along the floor of Echo Valley. Our guide had his Golden Retrievers with him and they splashed in the water. His dogs Nala and Yoshi have their own Instagram account (check it out).

The creek flowed from a wide tunnel. It took about 15 minutes to walk upstream through the cave, crossing the stream several times.

Another half hour of hiking and we reached a swimming hole with a small waterfall. Nala and Yoshi were soaked and muddied by now, so our guide gave them a bath.

Fifteen minutes beyond the waterfall we reached the village road and a small cafe that featured fresh fruit shakes, made from strawberry, mango, or guyabano (soursop). I liked the guyabano shake. It was only noon but I was a bit fatigued.

We retrieved the Toyota Avanza and drove back to Baguio in the afternoon. The drive back was foggy with plenty of trucks and we didn’t get back to Baguio until after dark. We had dinner at a healthy place named Green Smoothie in the SM City mall and checked into an AirBnB.

The next morning I bought local Baguio strawberries before boarding the bus to Manila.

All in all, a memorable road trip. If you go, Sagada will probably be much the same, even in a few years. It’s a bit of a mythic destination for young Filipinos. For foreigners, it’s just too hard to get there, except for hardy travelers. The closest regional airport is 5 hours away and Manila’s international airport is 12 hours away. With the Halsema Highway the only link to the globalized world, Sagada might maintain its uniqueness.

I've been part of building the web since its early days in 1991. Have something to say? Send email to daniel@danielkehoe.com. I'm currently working on the yax.com project for do-it-yourself websites.